An in-depth overview of how one of the greatest video games of this generation could be translated into a highly successful film trilogy.

(First published on November 14th, 2020. The latest revision was in May of 2022.)

The Harry Potter and Hunger Games films were groundbreaking epics that pushed the preconceived boundaries of entertainment aimed at the teenage and young adult audiences of their time.

With original stories that were more in line with independent cinema than the current trend of audience-tested institutionally crafted CGI thrill rides of well-worn intellectual properties, these films were, in essence, a low-level black swan event that defined the era from which they were created.

I’ve wondered how Persona 5 could be translated into a more traditional medium like television or film. After several years of research and development, I believe a project like this could not only be successful but, with its inherited subversive message and underlying “fight the corrupt power” storyline, could rise to become an actual connective cultural event for Generation Z, especially considering how the 2020s have seen massive changes in terms of geopolitics, social and political unrest.

Generation Z longs for something different as audiences become noticeably bored with reboots and remakes. Budget constraints and the ever-changing dynamics of streaming platforms will require studios to take more risks while being financially savvy.

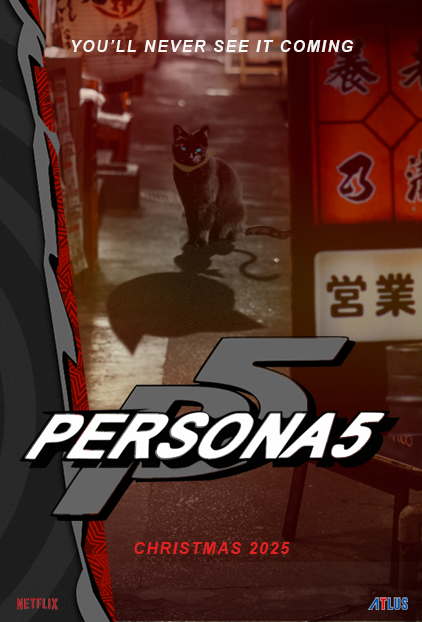

In the age of prestige television and endless streaming services, Persona 5, clocking in with nearly 100 hours of game-play, would appear to be better suited for a couple of seasons on Netflix. However, nothing fits the bill more than a solid motion picture trilogy when it comes to making the most cultural impact. A film trilogy allows anywhere from six to nine hours of story, which means you have to focus on only what is truly necessary and cut any extra material. Also, at that length, the entire film series can be easily digested and memorized by audiences, similar to Lord of the Rings and Star Wars.

Hence, Persona 5 should be developed into three films, similar to Lord of the Rings, with extended editions and a slew of bonus materials (which we will call “Mementos”) available for streaming later. Besides, we can avoid the infamous “Netflix Bloat” dilemma that many modern shows seem to suffer from. As this will be much smaller in scale, an indie variation of the standard blockbuster, extra care, and attention can be placed on cinematography and set design, which will be crucial for selling the story. As Persona 5 is considered by many to be a cult classic, a prestige video game, we will need to express this adaptation in a structure that would sustain the integrity of that admiration. This needs to be an adaptation with commercial potential that highly-elusive critical praise video game adaptations can’t seem to obtain.

No matter what, it’s going to be a tough sell, as the current “Citizen Kane” of films based on a video game is 1995’s Mortal Kombat. Even with recent commercial successes, Uncharted (2022), Mortal Kombat (2021), and most notably, Sonic the Hedgehog (2020), Translating video games into critically-acclaimed masterworks appears to be a near-impossible task. The simple reason, the material is poorly adapted and overly reliant on fan service. You cannot structure a movie plot around a video game. You need to strip the game’s narrative down to its basics and rebuild the story, using the different sequences and mechanics as a guide. The first Sonic film scored an impressive 63% on Rotten Tomatoes because it successfully subverted expectations and created an original story around the title character, wrapped in the lunacy of early Jim Carrey films, both of which arose to cultural significance in the 1990s.

Besides the typical issues adaptations face, this particular JRPG occurs in Japan. Learning the lessons from the cinematic mistreatments of Ghost in the Shell (2017) and Death Note (2019), the cast must be nearly all Japanese. This series must be filmed in Japan. We must be culturally respectful.

Let’s look at why video games are so difficult to translate into film or television.

As audiences are becoming noticeably bored with reboots and remakes, Generation Z longs for a game-changing franchise of its very own. As the world becomes more unstable over the 2020s, audiences will desire much more original content than what we’ve been given over the last decade. Studios will need to take more risks.

PLOT POINTS VS. GAME MECHANICS

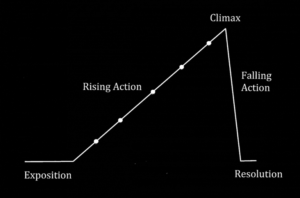

PLOT STRUCTURE… STEADY RISING ACTION

The narrative of most major motion pictures follows the same old plot structure pattern you learned about in high school. The rising action builds into a big climax between the protagonist and antagonist. Most of our favorite films leave a trail of breadcrumbs that help the viewer along. Like a magic trick, you tell the audience what you plan to do, and then you execute the scheme, doing precisely what you said you would do. The audience is delighted by the process and the ingenuity of the journey. The most critically acclaimed films will take more unusual paths towards that resolution.

The first part of a film tells you the plot and manages your expectations. The ending completes that journey satisfyingly by creating consistency in the narrative with a few surprises. Films also need to have a circular quality. The best movies start with visual cues and thematic elements that circle back to the end.

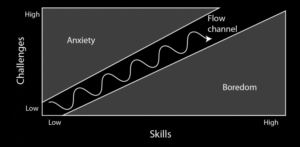

GAME STRUCTURE… A COMPLICATED AND NUANCED STAIRWAY

On the other hand, video games operate on a very different set of rules to keep your attention. As you are actively engaged within the medium, a steady rising action needs to challenge the player as they continue on the journey by keeping the difficulty wavering within a Goldilocks Zone, not too hard, not too easy. Boss battles act as mini-climaxes throughout the game, leading to the end battle, which is the last big fight.

You have to break apart the game-flow channel dynamics and reform them into a standard three (or five) act plot to adapt video games successfully. The pacing for a game you actively play is completely non-suited for an engaging drama you passively watch. This makes managing expectations extremely difficult. Also, since video games are driven by game mechanics and not necessarily narrative, if you try to jam too many of the game elements into the plot to please the fans, you’ll create a borderline incoherent film.

Sega Sammy has accomplished this task with Sonic the Hedgehog (2020). The next logical step is another video game adaptation that will achieve both commercial and critical success and finally break the notorious “video game” curse.

KNOW WHAT TO CUT AND WHAT TO KEEP

Most of what makes for great game mechanics is the steady repetition of push-button processes which slowly builds over time. We enjoy clicking the right set of buttons and getting a positive reaction on our screen. The gratification of mastering a particular technique on a controller is what drives video games. However, in video games, the pacing is challenging for the creators to directly manage as they hand that control over to the player. All you can do is nudge the player into choosing paths with a sense of urgency with good game design. (For Uncharted (2022), several mediocre film reviews indicated the unfair comparison of game mechanics and cinema.)

In video games, most exposition and story utilize cut-scenes, framed and executed more like a traditional stage play than cinema. It’s getting better, but they rarely flow well with the interactive parts of the game. Cut-scenes move the story forward with a lot of dialogue, and that’s about it, giving the player a well-needed break from mashing buttons. The action is usually shot wide, lighting and camera angles don’t factor into the segment simply because you don’t want to break too far away from the game-play aesthetic. In great cinema, camera angles, lighting, and cinematography can help tell the story, express a mood, subconsciously cue in narratives clues, and so on. Movies based on video games (and comic book movies) tend to carry over that bland stage play aesthetic and rely heavily on special effects and spectacle to make up for weak narrative choices. This is exasperated when dealing with Japanese video games that will eventually need to be translated into English.

Fortunately for us, Persona 5 has a lot of narratives and bold graphic styles to utilize. We have a lot of substance to work with. Knowing what to keep and what to cut is going to be critical.

CRAFTING THE STORY

Persona 5 is an extremely long game with a ton of story, which means you will have to cut out a bunch of stuff to make this work. This is the exact opposite problem most video games have. As Persona 5 has many subplots and diversions, you can quickly start trimming the narrative to its essential plot points and build from there. Those side quests, confidants, and questionable story choices can all be left aside or just briefly mentioned in passing, which can add more richness to the backstory.

The nice thing about the film is that you can cram a lot of information quickly through wonderfully crafted cinematography, camera techniques to frame intention or a dialogue-driven data dump as a last resort. You can express what it took an entire ten-minute cut-scene to do in the game in one carefully crafted shot.

A fun fact, in The Fugitive (1993), the famous scene where Harrison Ford proclaims he didn’t kill his wife, followed by Tommy Lee Jones giving a snarky response, “I don’t care,” was originally a few pages of dialogue. It was shortened to a couple of sentences and had far more impact. There are dozens of ways we can take the exposition from the game and condense them into brief but much more poignant scenes. When you think about it, the game has an unusual amount of explanation that repeats crucial information. (Persona 5 is such a long and detailed experience you need to constantly remind the player of the current plot points and objectives.)

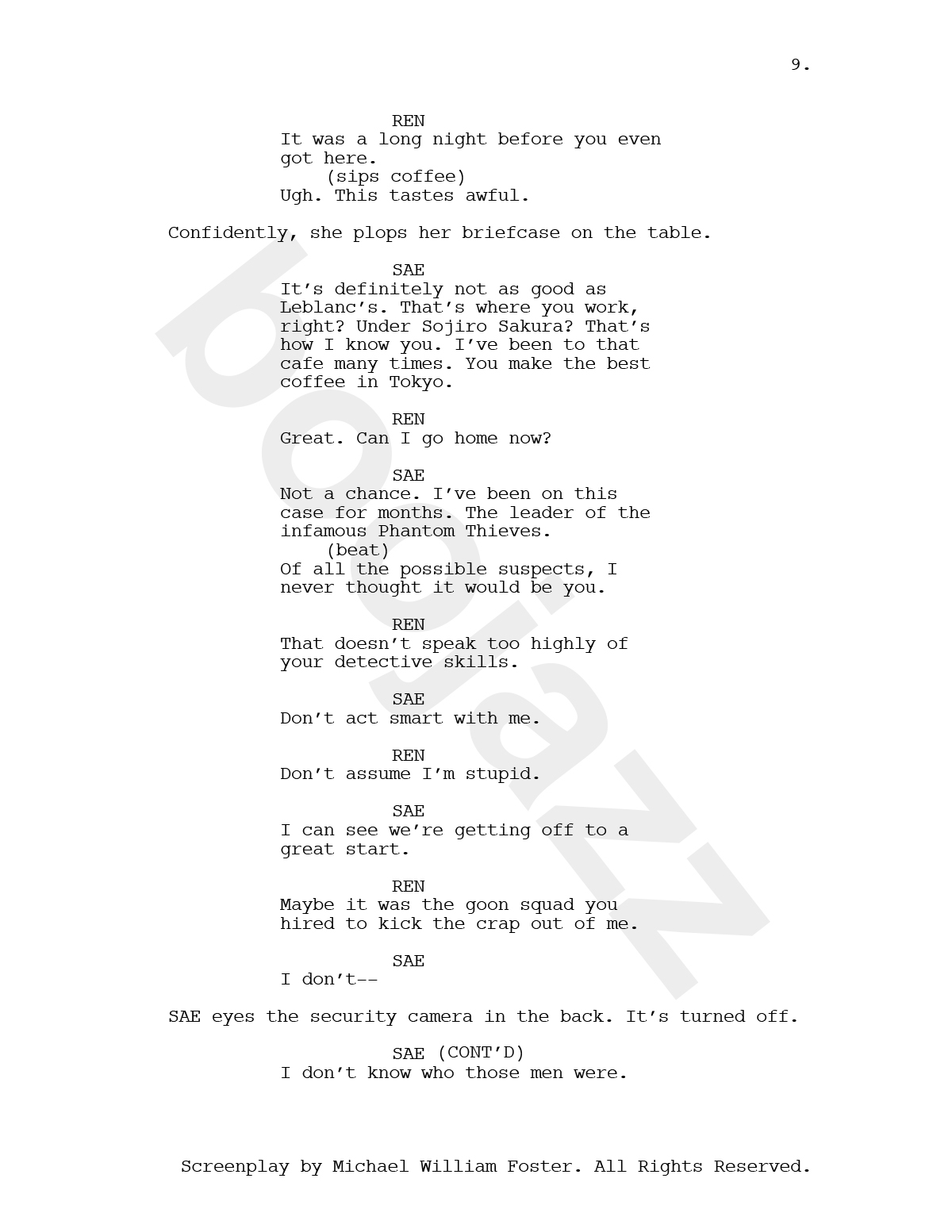

We can also take advantage of the fact that the first two films will be told from the perspective of the interrogation room, where our hero, Ren Amayima, can quickly sum up specific complicated plot points with investigator Sae Niijima. It’s a tricky balance when a movie (and in our case, the first two movies) will be told in backstory; you can easily lean too much on a narrator to drive the action forward. The movie will feel more like a string of stifled unrelated events driven by obtrusive voice-over than a solid, cohesive narrative with true momentum. And you don’t want to get too tied down to hitting non-essential plot points from the source material.

A lot of films like the Harry Potter Series, Atila: Battle Angel (2019), or the final two Hunger Games: Mockingjay (2014-2015) movies suffer a little from “got to please the fans” by including “everything but the kitchen sink” storytelling.

For those that will fuss and complain about the material that won’t make the film, that’s why you have the game and the animation. The movie adaptation needs to exist on its own merits; it must be its own thing.

For films, too much repetition can be a natural momentum killer. In terms of the nuances and mechanics the game utilizes to augment the action of the story; the baton pass, side quests, visiting other non-Phantom confidants, we just need to show them once or twice if they help drive the story forward. We can also re-purpose those elements as ways to push the narrative. You have hundreds of little quirks, gags, and gimmicks in the game that you can pepper throughout the film series and create a sophisticated layer of depth most franchises would kill for.

Using narrator-driven films like Rashomon (1950), Life of Pi (2012), The Usual Suspects (1995), and most notably, The Social Network (2010), as examples, most of the narration tells you just enough to set up the next scene with some suspense. We can leave the Morgana character to do any further necessary plot explanation while in Mementos, but always do so sparingly. Inception (2010) didn’t explain how dream-invasion technology works, and the film is better for it. Let the story’s action drive the plot, which the dialogue augments and embellishes.

As a director, I would shoot a lot of exposition and decide what is critical to add to the movie as we edit, always knowing that the less we have to explain, the better.

The Social Network (2010) is an outstanding example of intertwining interrogations, flashbacks, and explanations into the story that make several separate narrative threads flow as one. (The ping-pong writing style of a writer like Aaron Sorkin can significantly influence how the script will be developed.)

Developing the Films

THE BASIC PLOT POINTS

To set up the emotional drive to sustain three movies, the main plot points for the trilogy will be as follows…

• Ren Amayima overcomes his distrust of people and reluctance to become a leader.

• Makoto Niijima’s broken relationship with her sister.

• The Phantom Thieves assemble one by one, eventually conquering the metaverse and defeating the God of Control.

• Ren’s romance with Ann Takamaki.

In this complex story, you want to utilize the simplest and most emotionally driven story arcs. In the game, Ann shows up in the first couple of hours, and her storyline, which involves the physical and sexual abuse from a teacher that leads to the attempted suicide of her best friend Shiho, is compelling and moving. Even though Makoto is a fan favorite, she needs to fix her relationship with her semi-estranged sister and overcome her timid nature. Sure, we can play around with a love triangle between Ren, Ann, and Makoto. Unlike the game, where the Protagonist can participate in multiple romantic relationships, Ren is going to be monogamous for our movie. He’s the good guy, and for a film series that will ramp up the more unsettling story elements of the game, our hero needs to have a solid moral compass.

To The Point

1) Why do Persona 5? Why do a trilogy of films?

- The storyline is extremely relevant today. Rebelling against institutional corruption will be the primary running theme in the 2020s.

- Persona 5 comes with well-established characters, an original story, and a fully-realized fantasy world already developed.

- A trilogy of films opposed to a television series will help maintain overall production quality and increase the chances it can be viewed as a prestige project.

- Three movies and a coda. Persona 5 gets broken down into 3 (maybe 4) films with the events of Persona 5 Royal covered in a final chapter that acts as more of a standalone film.

2) Why is now the time to start making video game movies? Who would want to give a green light to this and why?

- The superhero genre has reached an over-saturation point.

- New ideas driven by counter-culture and more grounded “realistic” entertainment will be in fashion after the events of the pandemic and the consequences of a failed worldwide attempt to contain it.

- The Cool Japan movement may want to find new ways to gain cultural ground after a limited Olympic Games due to the coronavirus outbreak.

- A streaming service such as Hulu may want to break into the Japanese market with a flagship property.

- Asian films are a highly underutilized and undervalued market in the West.

- The 250 Million dollar blockbuster may not be a realistic option for a while. Studios are going to be strapped for cash and expensive movies are a very high financial risk.

3) Why have video game movies failed in the past?

- For starters, the spectacular failure of the Super Mario Bros. film (1993) has left a bad impression on converting video games into movies.

- To be fair, there are only about 50 movies based on video games. 1000 to 2000 films are released each year. That’s not a lot of data to work with.

- A true lack of understanding of how to translate video games into a film.

THE LENGTH OF ADAPTATION

Can this game will all of its content be condensed into a motion picture trilogy?

Let’s look at the numbers…

Persona 5 Game (Vanilla) Gameplay

Approximately 100 hours

Persona 5: The Animation

30 1/2 Hour Episodes

Approximately 15 Hours

Persona Film Trilogy Series

Each Movie could have a running time of 140 to 180 minutes, maybe longer for extended cuts.

Approximately 8 to 10 Hours

It can be done if the project is given the thought and consideration it needs.

Persona 5 Trilogy Outline

Film 1 – Persona 5

Cold Open: Failed Casino Heist / Interrogation

ACT 1: Ryuki Sakamoto & Ann Takamaki Storyline (Kamoshida’s Castle)

ACT 2: Discovering Mementos & The Velvet Room & Sadayo Kawakami’s Dilemma

ACT 3: Makoto Niijima Storyline (Kaneshiro’s Bank)

Closing Scene: Shiho Suzui & Ann Takamaki’s Resolution

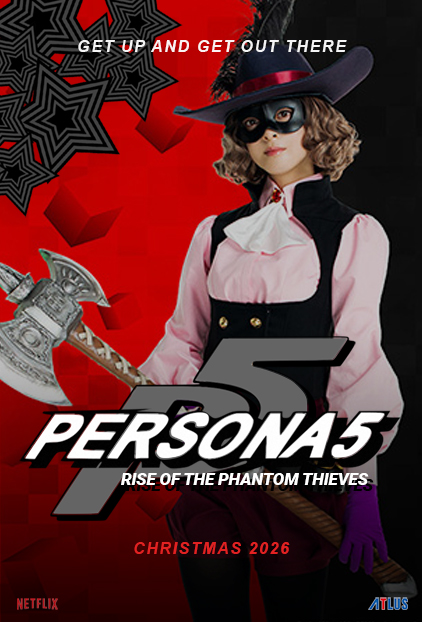

Film 2 – Persona 5: Rise of the Phantom Thieves

Cold Open: Yusuke Kitagawa’s Storyline Resolution (Madarame’s Museum)

ACT 1: Futaba Sakura’s Storyline (Futaba’s Tomb)

ACT 2: Haru Okumura’s Abbrievated Storyline (Okumura’s Space Station)

ACT 3: Aftermath & Goro Akechi’s Storyline (Sae Niijima’s Casino)

Closing Scene: Ren Amamiya’s Supposed Assassination

Film 3 – Persona 5: Persona Non Grata

Cold Open: Ren Amamiya’s Rescue (Team Regroups)

ACT 1: Masayoshi Shido’s Palace

ACT 2: Haru Okumura’s Resolution, Kitagawa’s Art Show & Election Results

ACT 3: Face off with Yaldabaoth, the God of Control

Closing Scene: The Thieves Drive off into the Sunset

REN, THE PROTAGONIST, NEEDS TO BE A REAL CHARACTER

In the video game, the main protagonist, Ren Amiyama, is designed as a blank slate since players will subconsciously embed their personality traits into that character. This is what makes the game so compelling. Ren has to be a fully fleshed-out individual to make the film work. A successful character arc would include Ren overcoming his reluctance in the role of leader. As a director, I would have the actor study Tom Hanks in Saving Private Ryan (1998) and many other flustered reluctant leaders from movies. Seven Samurai (1954) seems like an obvious choice for reference points here, as it invented the “let’s assemble the gang” genre. When unsure how to proceed, We can always draw upon the source material for Ren’s persona, Arsène Lupin, or any of that character’s design elements.

For example, since Ren’s haircut was inspired by the rebellious British Invasion bands of the 1960s, the character can listen to Japanese garage bands from that period, such as The Mops, The Bunnys, and The Spiders.

Ren, a loner by default, feels a general sense of honor and duty but hates feeling saddled by his conscience. In the flashback scene, where Ren prevents the main antagonist, presidential candidate Masayoshi Shido, from committing sexual assault on an unnamed female victim, he should initially be reluctant to come to the rescue. We can show a few window lights in the neighborhood shutting off; an older man in the distance quietly peeks out the front door but won’t interfere. This is where Ren’s character arc begins. He’s torn between a sense of moral obligation to his community and his reluctance to get involved with others, unfairly punished by his good intentions.

Ren should also be a little sarcastic and elitist. It’s his defense mechanism. His character should be a bit skeptical of everyone’s intentions. He’s a little like Tetsuya Hondo in Tokyo Drifter (1966). He’s not as jaded, but he’s getting there.

Hence, Ren becomes much more trusting as the story moves forward. Since the main narrative involves him becoming the leader of an ever-expanding band of thieves, it only makes sense to have a character arc that works within the primary function of the story. Ren needs to start the story as someone who never really had many friends. His unfair arrest and probation made him even more introverted. By the end of the third film, he rides off into the sunset with a group of people he’s become close to. That’s his journey.

PERSONA SUMMONING DYNAMICS & DYNAMIC ACTION SEQUENCES

The game mechanics of Persona executions, mixing, and matching Personas will have to be condensed. Ren gets the initial Arsène Persona at the beginning, which he’ll work with. Personas will be summoned by the characters when there’s a specific need. Trying to cram all of the technical fighting turn-based mechanics as they are built in the game will not work for a feature film.

On the other hand, characters experience significant pain when first summoning a Persona. That definitely should be carried over into the films. When the characters summon their Persona, that Persona manifests to perform a specific task and then quickly disappears. They could summon a Persona to bust through a wall or deal with an enraged enemy they don’t want to mess around with, but it always comes with a bit of physical self-punishment. Persona summoning needs to feel visceral. Every time they rip off their mask, it always needs to hurt a little. The notion that if a Persona is injured, it also simultaneously hurts the character in control is a good idea.

From a visual special effects perspective, we can use the creatures that are summoned in the movie Scott Pilgrim Vs. the World (2010) during the Amp vs. Amp battle while mixing in a little bit of the avatar design in Ready Player One (2018) and the kinetic live-action version of Bleach (2018) as excellent visual reference points to draw from.

Since this is a live-action adaptation of a new property, there are more than likely some budget constraints. (If the first film is successful, then the sequel films can slightly ramp up the budget and special effects.) The game mechanics of a JRPG are impossible to film; that part is a given. The physics won’t make sense. Why would Ann even bother to use a whip if the characters have guns unless a situation warrants it explicitly? Or what about Haru’s Persona? She carries what is essentially a hidden battleship gun. And eight characters fighting one lumbering big bad doesn’t make for the most original battle sequence unless you go with the Marvel method of slathering CGI all over the screen, which is tedious and expensive. There isn’t going to be a budget for that regardless. This isn’t an action series; it’s more of a screwball comedy-inspired heist thriller with some action sequences. There’s a difference.

As for weapons, the characters will purchase them in the real world but have to physically bring them into the palaces (they won’t just magically appear and disappear). This sets up a bit of tension, as the characters are essentially carrying around bulky illegal items in the real world, even if, in some cases, they are just replicas. There is always a chance of them getting caught with contraband. Any small way you can logically increase tension in the story, the better.

Action sequences and boss battles will need a cinematic structure to make them realistic. For example, portraying Kamoshida’s evil form as a giant monster drinking from a goblet of women’s legs will be challenging to adapt to a live-action version that makes logical sense. There are ways to incorporate more logical character design elements in a fight using the video game elements as a starting point. In the game, Kamoshida hurtling high-speed volleyballs works well because it serves the personality and backstory of the character. That makes sense. Kamoshida’s transformation into a giant lumbering monster, not so much.

Maybe Kamoshida’s evil form is more human-sized; he’s quick because he’s an athlete. He still has that goofy goblet that gives him power, but perhaps he still creepily chomps down on small little figures of women for that extra kick of energy. Ann could then use her whip to yank the goblet out of his hand, symbolizing her stripping/punishing Kamoshida from his lustful ways. Morgan summons his Persona to manifest wind to blow the goblet away from Kamoshida. Ryuji summons his Persona, Captain Kidd, riding a pirate ship as a surfboard, pivoting and whacking Kamoshida down; Ren opens fire with his pistol. Still, Kamoshida* quickly gets up, summons, and fires off a volleyball. Ren ducks, but it still smacks Ryuji in the head. Having a logical series of events makes it all so much more dramatic. All of this happens within a few seconds and in low-lighting, helping with CGI rendering issues that might occur when working with a lower budget.

*Please note: In earlier drafts, Kamoshida was mislabeled as Kaneshiro. We apologize for the error, but we think the real Kamoshida might have had something to do with it… (insert laugh here)

In conclusion, the characters all have well-established means of fighting in the game. We will have to find ways to make them work and function in a more realistic setting. Scaling up or scaling down various combat elements of the game will help create an equilibrium that makes sense in a fantasy world still governed by real-world physics. And in the end, each action should inform the audience something about the character, no matter how small. Each scene needs to move the story forward.

HOW TO ACCURATELY PORTRAY A TALKING CAT

This is also tricky. In the game, Morgana is a small animated humanoid character unless he finds himself in the real world, where he’s portrayed as a more realistic talking cat. A talking cat is a natural stretch that could lose the audience for obvious reasons. Even Netflix’s Sabrina reboot skipped the talking cat gag altogether.

The best treatment would be for Morgana to be a non-speaking cat in the real world. Still, he can communicate in other ways, primarily by his body language, the occasional meow, or gesturing toward items of interest. This will make Morgana’s sacrifice at the end of the third film more poignant. When the alternate metaverse collapses, Morgana will give up his ability to be the more communicative humanoid version of himself. Even though he longs to be human, he will be stuck as a cat for the rest of his life.

SAMPLES FROM A SCRIPT

CINEMA

The movies we can draw inspiration from to create the Persona 5 Trilogy are as follows…

The Great Beauty (La grande bellezza)

Directed by Paolo Sorrentino • 2013

For pacing and cinematography, cram a lot of information in a well crafted sequence

Amélie (Le Fabuleux Destin d’Amélie Poulain)

Directed by Jean-Pierre Jeunet • 2001

Also for pacing and cinematography

Shoplifters (万引き家族)

Directed by Hirokazu Kore-eda • 2018

For all of the quieter moments, classroom scenes, emotional dialogue

Inception

Directed by Christopher Nolan • 2010

Cinematic ways to demonstrate a heist

Ocean’s Eleven

Directed by Steven Soderbergh • 2001

Entertaining ways to balance an ensemble cast

Let’s also consider the following for inspiration…

Chunking Express & Fallen Angels

Directed by Wong Kar-wai • 1994 & 1995

Irma Vep

Directed by Olivier Assayas • 1996

Like Someone in Love (cinematographer Katsumi Yanagishima)

Directed by Abbas Kiarostami • 2012

Scott Pilgrim vs. The World

Directed by Edgar Wright • 2010

The Young Rebels

Directed by Keisuke Kinoshita • 1980

Battle Royale

Directed by Kinji Fukasaku • 2000

Crazed Fruit

Directed by Kô Nakahira • 1956

Diary of a Shinjuku Thief

Directed by Nagisa Oshima • 1969

Still Walking

Directed by Hirokazu Kore-eda • 2008

The End of Summer

Directed by Yasujiro Ozu • 1961

Tokyo Story

Directed by Yasujiro Ozu • 1953

Rashomon

Directed by Akira Kurosawa • 1950

Lady Snowblood

Directed by Toshiya Fujita • 1973

Drunken Angel

Directed by Akira Kurosawa • 1948

Tokyo Drifter & Branded to Kill

Directed by Seijun Suzuki • 1966 & 1967

MUSIC

Besides the wonderful Lyn Inaizumi, who else can we put in the soundtrack?

Otom

And Lorelei

Browned Butter

Haiku Garden

Yuragi

Wednesday Campanella

Glim Spanky

Akkogorilla

Chai

Aya Gloomy

BiSH

Mondo Grosso

Daoko

Kaho Nakamura

DYGL

Domico

Denims

Boris “Pink” Album

Hiroshi Yoshimura

Soul Survivors

The Dave Clark Five

Idles

The National

Algiers

Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah.

LITERARY REFERENCES

Ann Takamaki could pop out of a bakery in Kichijoji as an homage to Moshi Moshi by Banana Yoshimoto

In LeBlanc Coffee, you could have the May/December couple from Strange Weather in Tokyo by Hiromi Kawakami chatting in a booth.

One of the palaces could have two moons in a reference to IQ84 by Haruki Murakami

In the famous spying sequence, Makoto Niijima could have her face buried in either Breasts & Eggs by Mieko Kawakami or The Devotion of Suspect X by Keigo Higashino.

Someone should be reading Out by Natsuo Kirino at some point… maybe it’s a book on Ren’s work desk.

PRODUCTION & LOGISTICS – IN BRIEF

Let’s do a quick review of a tentative shooting schedule. It only makes sense to shoot all three films simultaneously. You have to plan for at least four to six weeks of shooting on location in Tokyo itself. As Tokyo is notorious for not allowing film permits, you’ll have to catch a lot of stuff on the fly or recreate notable areas on set. You’ll also want to get a few B-roll shots of Shinjuku square and several sequences in the subway system.

You’ll want to use the locations that occur in the game with their real-world equivalents, adding a layer of authenticity. For Shujin Academy, let’s find an abandoned school where we can renovate to film interiors and exteriors.

If there is an abandoned school we can renovate for on-location shoots, it will make sense to convert that school into multiple sets for other locations. The SIU Director’s office, Ren’s Bedroom, Untouchable, Takemi Medical Clinic, and even Leblanc Coffee could be built in former classrooms on the school grounds, converting the building into one large production studio.

Most palaces will have to be on a virtual set, as the budget would not be enough to shoot in real castles, casinos, or pyramids. An Unreal Engine-driven LCD set can be used to recreate these environments. Since palaces take place within a “fantasy” world, the Unreal Engine platform can creatively augment or exaggerate the environment. The difference in look and feel compared to the “real” world settings would help sell the story.

Since the neighborhood of Sangenjaya was the basis for Cafe LaBlanc’s location, we can utilize this to significant effect. The characters spend so much time in that neighborhood, and it’s much quieter than Shinjuku. You can quickly get shots there. Also, it’s not too far from Atlus Headquarters in Japan.

CINEMATOGRAPHY

The game does a lot of exciting things with angles and corners. There’s a natural tilt to the world the characters inhabit, augmented by the UI/UX design of the menus. There are a lot of zigs and zags.

As a rule, I would have my cinematographer shoot much of the first movie using Dutch angles. As the film series progresses, the camera angles lessen. Everything is straight on and level by the end of the third film. It would be a simple but highly effective way to show how the world of Persona 5 is slowly rectifying itself due to the main characters’ actions.

In terms of color and lighting, for the real-world scenes, I would draw heavily on films like Lost in Translation (2003) and Shoplifters (2018). The real-world needs to feel soft, painterly, and pastel except for the color red, which will highlight specific locations and objects, just like in the films The Sixth Sense (1999) and Three Colors: Red (1994). We can shoot in natural lighting and use post-production to augment the red hues.

When characters find themselves in the metaverse, you’ll get all of the neon, colorful lighting techniques they use in films like John Wick 2 (2017) or Tokyo Drifter (1966).

All of the later period yakuza films directed by Seijun Suzuki would be an excellent inspiration for colorful action in the metaverse. (Tarantino has gotten a lot of mileage from the visual style of films like these.) Regardless, bright, moody lighting is a great way to make sets look more exquisite and hide flaws, especially when you’re on a budget. An entire cinematic look was invited just for that reason. In Blade Runner (1982), director Ridley Scott was so disappointed by the set design he only shot in the dark with lots of smoke and minimal lighting to hide the poor quality of the location.

Of course, you really can’t do a Japanese film series justice without having a series of visual references to Ozu and Kurosawa. The far establishing shots of Kurosawa can help frame the palaces in a way that seems natural, mysterious, and intimidating. For the character interactions, Ozu’s framing of shots (Wes Anderson borrows a lot from this atheistic) can help make those interactions visually exciting and keep the audience focused.

Good cinematography can instantly show how a character feels without resorting to lengthy exposition. We would be making a critical mistake if we didn’t pay homage to several classic Japanese directors like Akira Kurosawa in framing the sequences.

SOUNDTRACK & INTERIORS

As for the original music, it’s fantastic. Shoji Meguro did such a tremendous job; there’s no reason to rewrite any of it. We will undoubtedly re-record or rework the original music with an orchestra, but we have everything (musical cues and themes) we need. It would be interesting to hear slower versions of specific tunes. “Beneath the Mask” performed by a music box is downright haunting. Finding new ways to express the music established in the video game will surprise long-time fans that have already memorized the tunes from hours of gameplay.

Persona 5 comes complete with richly developed music and art direction. All significant set design work has already been finished for the video game and animation from a pre-production standpoint. I imagine from an artistic perspective; you will want to make very few changes except translating the spaces to best suit the cinematography, which will be determined by the way the action sequences evolve in the script. The only real caveat would be to ensure that much of the set design is more of a labyrinth, too narrow to allow for the gag when Morgana transforms into a van. Also, more compact spaces make for much better and more contained thrilling suspense sequences. Each Palace will need its own set, although a clever set design team can re-purpose textures and some props from one set to the next. There’s also a case for utilizing virtual LCD sets where applicable, especially for the inevitable reshoots, but the more you can get on camera, the better. Special effects are expensive, and there will be several creatures developed in CGI as it is.

Scouts would find several locations worldwide and shoot there in the most idealistic circumstances. Unfortunately, that will probably be out of the question for a movie series with a far more limited budget, which I imagine this project would have. You’ll have to send a second unit crew to scout locations and grab those cinematic opening shots of Futaba’s pyramids in Egypt (the only actual location outside of Japan) and other sites around Tokyo. Because the set pieces will contain a lot of action sequences and visual effects, you’re probably going to want to allow for at least four to six months of shooting.

Once all of the scenes are shot on the sets, you fly back to Tokyo to get any remaining location shots you didn’t grab the first time around. The crew can start taking apart the majority of the sets but leave sections behind so you can get the reshoots you’ll need when you start editing the films together.

If you want to make a profit from a financial standpoint, you’ll want to see if you can complete all three films for under $250 million US. You want a theatrical release accompanying an exclusive streaming contract roughly two months after each film opens worldwide.

It’s a really interesting time in Japan right now for cinema, and Japanese studios are looking for big box office success stories. Although there are still major differences between Japanese and American sensibilities, a perfect combination of those two cultures can lead to something new and exciting. We’ve been borrowing and stealing from each other for years, it’s about time we worked in unison on more creative endeavors.

I’m not placing comments on this post but feel free to write to me directly. I’d love to know what you think… just email me.

If anything, what I hope this synopsis expresses is not that my own ideas are necessarily the best, or this is exactly how to translate Persona 5 into a film or a television series… but that a Persona 5 film series is a really good idea and far more feasible that one might initially think. When you start digging deep into the main story, which is simply brilliant, you can turn this into something special. There’s been animation and a stage play, a film series seems like a logical next step. Maybe video games will finally have their moment in cinema, it’s been long overdue. By breaking up the story, stripping it down to what drives it the most effective, then rebuilding it using all of the hard work Atlus has already completed, you can create something that works as a film while truly honoring the original source material. And if this all of this helps gain some momentum for a film adaptation, it would be a job well done.

Michael William Foster

(Just One More: I wrote this article for fun as an editorial about film and the tricky nature of adaptations. I’d like to thank Atlus and the gaming community for much of the material which acted as an inspiration for this article. If you haven’t bought Persona 5 Royal, you should.)

LESSONS IN MOVIE MAKING

For the Criterion Channel on FilmStruck, filmmaker Daniel Raim took a pilgrimage to Japan to get his own firsthand look at some of the most iconic objects in the world of Yasujiro Ozu.

“How Wong Kar Wai used Step printing to dramatize moments in his movies. We explore why Chungking Express, the less famous sibling of In The Mood For Love, is nonetheless powerful and transcending.”

A lesson in how to find humor through framing, camera movement, editing, sound effects and music.

Framing techniques for the 2000 film “In the Mood For Love”

“Perhaps the only thing more fun than watching a perfectly executed cinematic heist unfold is watching it unravel, as evidenced by twelve safe-cracking classics now playing on the Criterion Channel.”